- Home

- Jimmy Thomson

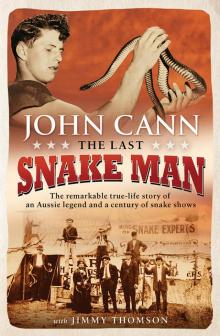

The Last Snake Man Page 22

The Last Snake Man Read online

Page 22

Belle herself received a few scratches from fangs but only one proved serious. She was bitten by a tiger snake, and although antivenom was available at the time it was not on hand when she was admitted to hospital. Fortunately, she’d received a nonfatal dose of venom.

In 1939 the Wades broke their partnership, professionally and personally. Belle retired from the snake pits and Fred took on another woman snake handler, whose show name was Jedea.

That Man Gray

Back when the Greenhalghs got into the snake acts, permanent shows in the city proper were another feature of Sydney life. In 1916 a youthful George Cann rented a shop at the railway end of Elizabeth Street and installed a pit. At the other end of the city, on a vacant lot next to the Lowes store, a well-known showman referred to as ‘That Man Gray’, rented a patch of ground from the council, erected frames, hung his snake pit inside and set up business.

As usual, a legitimate snakey like That Man Gray attracted conmen and charlattans, and in all likelihood one of them was one George Vowels. In February 1917, the Sydney Morning Herald reported that a crate of snakes had fallen from a cart in George Street and that one of their captors had been bitten by a venomous snake. Eighteen days later, on 5 March, Vowels, a snake-oil salesman (or antidote vendor) was bitten by a 1-metre tiger snake. He died 23 hours later.

Tests were carried out on the snake and it was stated that both fangs had been damaged (for which read removed) before Vowels was bitten. Removal of fangs is no guarantee, however, that you won’t come in contact with the venom if your skin is broken by the stumps.

There were reports at the time that one of Vowels’ previous partners, Barnett Alvarez, had died in the same manner about a month before, though his death certificate reveals that he died a full year earlier, on 15 March 1916. ‘That Man Gray’ was later to die in a mental hospital.

The Millers

The name Miller figures largely in early twentieth-century snake shows. Among them was one John Miller from Queensland. In 1922 he went to Cohuna in Victoria and gave several exhibitions with tiger snakes he had caught on Gunbower Island in the nearby Murray River. One Sunday afternoon he was bitten on the hand during the show. He refused to have it cut by those present and expressed professional confidence in a remedy of his own. It was a full 24 hours before Miller collapsed; he died the following morning.

The famous handler Fred Miller (no relation of John’s) worked the pits under the name ‘Milo’. He was bred into showbiz; his mother Alice, who worked the snakes as ‘Necia’ and ‘Esmerelda’, was possibly the only snake woman to ‘accept the bite’. His father was another snake man, and he married a show lass, Amy Ferguson, who also took to the canvas pits.

Another related Miller, Charlie, worked the pits as ‘Marco’ and ‘Marlo’, and quite a number of old showies remember him as ‘a wild man with a wilder mouth’. Like Milo, he was a good handler, although he had many lucky escapes with bites. A news report of the time tells of Marlo Miller being bitten on the arm and forehead by a tiger snake. He took little notice of it, though the effects soon took hold and he was admitted to Wangaratta Hospital in a serious condition. Both Milo and Marlo had built up resistance through numerous earlier bites, so neither was claimed by snakebite.

Pegleg Davis

In his book Song of the Snake, Eric Worrell talks of one ‘Pegleg’ Davis (also recalled by my pop). Where Davis operated from, and for how long, is lost in the mists of history and failing memories, but it’s said that he was in the habit of attaching deadly tiger snakes to his wooden leg…until one struck him on his good leg and killed him. It’s possible that Pegleg was around just long enough for his name to be recalled, though it must be admitted that the story has the ring of a ‘campfire yarn’.

Abdullah and Ram

Nazir Shar began his fairground career running boxing kangaroos and appearing as Abdullah the Indian Mystery Man. But in 1943 he switched to snakes and trained another performer of Indian extraction, Ted Ramsamy. Shar and Ramsamy parted ways in 1945, and Shar moved to the Northern Territory, where he operated a small private zoo in Darwin until his death in 1972.

Ramsamy, however, changed his name to Ram Chandra in 1946 and, billed as the ‘Indian Cobra Boy’, kept on chasing the crowds. In 1957 he became one of the few people ever to survive a taipan bite, but he was perhaps lucky even to survive to the 1950s.

In 1948, Chandra was booked to perform at the Sydney Easter Show and contacted Pop in his capacity as curator of reptiles at Taronga Park Zoo. Pop filled an order for a number of tiger snakes for Chandra’s ‘Pit of Death’. It was Chandra’s first encounter with tigers and, being unfamiliar with their low, gliding strike, he was bitten on his first show day and was soon in hospital fighting for his life. Antivenom pulled him through, and the following day he was back in the pit, only to be bitten once more. The effects of the second bite were less pronounced, and it seems likely that the serum still in his system was sufficient to counteract the venom.

In 1975, Chandra was awarded the British Empire Medal for his work in collecting taipans and venom for the Commonwealth Serum Laboratories. In many ways he successfully straddled a spectrum of ‘snakey’ behaviour—from the charlatans and snake-oil salesmen at one end to the collectors, exhibitors and researchers at the other, united in the ‘science of show’.

Snake women of renown

And, as I have touched upon here, it wasn’t just snake men who drew the crowds, and given that my own mother was one of a long, long line of Cleopatras, I could not fail to acknowledge some of the great snake women of the pits. Some, like Belle Wade, as you have read, were part of teams with their husbands. Others, like Latiefa and Indita, were exotic imported solo performers.

Fred ‘Milo’ Miller’s manager, Captain Gus Leighton, married a show lass, Amy Ferguson, who also took to the canvas pits. Norma ‘The Wonder Woman’ and Shane ‘The Wonder Girl’ Brophy, the stepmother and stepsister of Fred Brophy of boxing-tent fame, both served their time in sideshow snake pits.

We first hear of Zillah, the Tasmanian Bush Girl, in a newspaper article from Tasmania reporting how a spate of snake-handler deaths was about to lead to the practice being banned. Readers were advised to see her show at Hobart’s Regatta Ground before the plug was pulled: ‘It seems rather likely, in consequence of a recent lamentable death, and the fact that during the last 12 months no fewer than nine professional snake charmers have paid a fatal penalty for their temerity, that this type of show was due to be closed down,’ said the story.

Zillah was Tasman Bradley’s daughter Peggy Goodrick. Tas was my great-uncle and it was he who also got his niece—my mother—into the pits as Cleopatra. Both Peggy and her husband Vic were in showbiz. She worked as a handler for a few years, finally giving the dangerous side of the business away after the Sydney Easter Show of 1920. But the shows were in Peggy’s blood, and she and Vic continued their working lives around the circuits and the snake pits. One of their unfortunate handlers, the teenage Jimmy Murray, died when a black tiger snake bit him at Smithton, Tasmania.

Another female snake handler billed as Cleopatra was less fortunate than Zillah. Theresa Caton came from Cunnamulla and was only 27 when her luck ran out at the Manly Beach carnival on 12 March 1920. She was bitten on the finger, not by an asp like her historical namesake but the much deadlier tiger snake, and died the next day. And, as if pursued by fate, both her partners, Anthony Kimbel and Tom Wanless, were to meet similar ends in the following months.

Alf Brydon, his wife and son—all of them snake handlers—travelled to Rockhampton in 1927, where Mrs Brydon was bitten through thick riding breeches just above the knee, and died within twelve hours. She had been demonstrating a previously milked brown snake.

Snake handler Snowy Pink had the pits going strong in the 1920s with Ada, also billed as Miss Kittyhawk, doing the honours, though later she moved into fortune telling…Maybe she’d seen her future. Snowy also had an attractive daughter, Thelma, who was only sixteen when she began h

er career as ‘Vonita the Snake Lady’. Venomous snakes were included in her act, and it was almost inevitable that sooner or later she would be bitten. When it happened, however—at the 1928 Lismore Show—the circumstances were unusual. A wild windstorm partly demolished the sideshows, and Thelma was hastily collecting escaped snakes when a red-bellied black—fortunately not the most venomous of snakes—hit her on the hand. She collapsed later and was taken to hospital, where she soon recovered.

In 1922, at the tender age of twelve, Alexie Le Pool got involved in snake shows, working for her father Charles until his death in 1928, then staying with snakes for a further five years.

One of the most attractive of the snake-show performers at this or any other time was Paula Perry. Born Paula Pratt in Lismore in 1912, she became a versatile show performer, starting out on horses at the age of seven and later taking on lion taming, trapeze work and striptease. She married Mick Perry, toured New Zealand, and in 1942 was performing in Manila when the Japanese sweeping through the Philippines overtook her. After more than three years of internment, she went straight back into dancing, performing at Sydney’s Celebrity Club.

Aged 35 but looking a good fifteen years younger, she was a Pix magazine cover girl in February 1947, and an article in the same issue told of her introduction to snake handling, learning from Pop on his La Perouse pitch. She then diversified even further, working under her own name, as Paulette the Fan Dancer, and in the Pit of Death with both the Wades and Greenhalgh and Jackson.

In 1948 she had a disagreement with Greenhalgh, claiming: ‘Arthur wanted me to exaggerate the facts about snakes. l wanted no part of it. He also insisted that I speed up the talks as those present would not move around the boardwalk, and this caused some of the waiting customers to wander off.’

After twelve successful years of tent shows, Paula travelled the world, often receiving top billing in nightclubs as the feathered expressive dancer the ‘Ostrich Girl’. In 1973, Pix ran an article on the youthful 61-year-old, still a fan dancer and high-kicker, performing with the eighteen-year-olds in an all-girl revue.

The question remains: why did she ever feel she needed to work with venomous snakes? It’s not as if she needed to add to her appeal. But then again, Paula never did anything by halves.

There are many, many more snakeys than I have recalled here; if you want to read about them too, you’ll have to track down a copy of Snakes Alive—if you can find one.

APPENDIX

JOHN’S TURTLES

In my time, I’ve discovered and/or names several turtles, as listed below. Some of the genus names have now changed but these are the names I gave them.

Discovered and named

Chelodina kuchlingi Kuchling’s turtle, named for Dr Gerald Kuchling.

Elseya irwini Irwin’s turtle, named for Steve Irwin, Queensland.

Elseya georgesi Georges’ turtle, named for Dr (now Professor) Arthur Georges, ACT (now called Wollumbinia georgesi).

Elusor macrurus Mary River turtle, Latin for ‘the most elusive’, referring to the long hunt for its discovery.

Emydura tanybaraga Northern yellow-face turtle. Given the local Aboriginal name of a female adult turtle in the Daly River, Northern Territory, by the Ngangi Kurunggurr Group.

Rheodytes leukops Fitzroy River turtle, Latin for ‘white-eyed river diver’.

Six new subspecies

Some of these were well known but undescribed as distinctive, different subspecies for nearly a century. As noted earlier, some scientist don’t recognise some of my subspecies, but hundreds of scientists both in Australia and worldwide accept them.

I’m known as a ‘splitter’ rather than a ‘lumper’, and it’s the lumpers who don’t believe in my subspecies. When Professor Legler studied our turtles and first encountered the coastal Emydura, he thought they were different enough to be considered full species. In the past, I forwarded to the Australian Museum one of John Legler’s letters using the name Emydura canni for the Macleay River turtle. John never got around to naming the turtles he intended to, but others, including me, have.

Emydura macquarii dharuk Sydney Basin turtle, named after Aboriginal people who lived in this region.

Emydura macquarii gunabarra Hunter River turtle, given the Aboriginal name for the river.

Emydura macquarii dharra Macleay River turtle, named after the Aboriginal people who named the turtle.

Emydura macquarii binjing Clarence River turtle, named after the Aboriginal people in the upper reaches of the Clarence River.

Emydura macquarii emmotti (named with Bill McCord) Emmott’s turtle, named after Angus Emmott of Noonbah Station, south-west Queensland.

Emydura macquarii nigra (named with Bill McCord) Fraser Island short-neck turtle, named for its normal black colour.

Rediscovery

Elseya bellii I rediscovered this species after it was found in an English museum, having been described in 1844. I was informed by photographs sent to me by Anders Rhodin (United States) and historical evidence of where the original came from.

Natural hybrid species

In 1989 I found a dead turtle on the road, in North Queensland Gulf Country, north of the Fitzroy River. This led me to another interesting find which was the meeting point of C. longicollis and C. rankini—a tremendous blend of all species in shape. Another most interesting form is a hybrid, a long-neck turtle which I collected in North Queensland Gulf country. I was convinced it was a new species. Genetic tests by (then) Dr Arthur Georges of the University of Canberra proved it to be a hybrid between the northern long-neck turtle (C. longicollis) and Cann’s turtle (C. rankini), which saved me the embarrassment of claiming it as a new species. This most fascinating long-neck turtle is a tremendous blend of all species in shape.

These two different genuses of turtle are obviously breeding by themselves at two different locations, and hybridising where they overlap. I’ve been told by an American expert that for this hybrid turtle to be accepted as a new species, it must be found living and breeding for successive generations in different locations, which has now occurred in a lagoon in the same river system.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

I’d like to thank Keith Smith, whose two volumes of memories, published under the title Johnny Cann: Nature Boy, provided an inspiring treasury and invaluable road map for this book.

I also thank Ross Sadlier, whose work with me on turtles, especially my photographs, has been outstanding, and Steve Swanson, who rescued and enhanced my ageing pictures.

I want to thank my grand-niece Rachael Cann for helping me turn my thoughts into written words.

And I want to acknowledge the work of Jennie McCulloch, who transcribed hours and hours of interviews without flinching.

Kelly Fagan at Allen & Unwin deserves credit for coming up with this project, and Angela Handley my gratitude for taking it from manuscript to printed book.

And finally, thanks to Jimmy Thomson for weaving all the threads of my life together.

INDEX

Abdullah the Indian Mystery Man see Shar, Nazir

Aboriginal people 4–5, 30–1, 37, 79–80

1967 referendum 82

Exemption Card 82

racism 71, 78–82

Aboriginal Reserve 19

Aborigines Welfare Board 82

Abramovitch, David 102

Ada 287

Agostini, Mike 72

Allen, Trevor 194, 240–2, 244

Alvarez, Barnett 282

antivenom 21, 123, 130–1, 138, 141, 145, 212, 281

allergy 137, 142, 145

development 132

immunity of snakes 133

polyvalent 133

specificity 133

Ardler, Ali 217

Atkins, George 12, 18

Australian Museum 10, 120, 128, 155, 292

Australian Reptile Park 20, 123

Australian Rules football 40–1

Bare Island 4, 122, 241

Bartlett, Freddie 86–

8

Bell, Roy 83–4

black-market animal trade 236–9

Bradley, Matilda 14–15

Bradley, Tasman ‘Tas’ 13–14, 16–17, 27, 286

Bringenbrong Gift 75–6

Bromhead, Gary 68

Brophy, Norma ‘The Wonder Woman’ 285

Brophy, Shane ‘The Wonder Girl’ 285

Bruce, Ian 56, 60

Brydon, Alf 287

Bubb, Elizabeth 14

Bubb, George 14–15

Bunnerong Power Station 37–8

Burger, John 266–8

Burns, Neville 214–15

Butchart, Bill 68

Caltex 109–11

Campbell, Milt 60

Cann, Belinda ‘Bindi’ 23, 103, 169, 221–2

Cann, Ellen (grandmother) 1–2

Cann, Essie xiii, 13–14, 19–20, 128, 131, 286

antidote manufacture 22

show name xii, 13–14

snake-handling 15, 18, 27, 279

wedding 17

Cann, Frank 2–3

Cann, George (father) xi, 15, 17, 19, 278, 281

antidote manufacture 22

birth 2

character 27

death 131

education 27

first snake show 7–8

knowledge of snakes 17, 26–8

marriage 17

New Guinea Taipan (Oxyuranus scutellatus canni) 134, 137

origins of snake interest 3, 6–7

retirement 21

scientific reputation 20

showmanship 20, 27

Snake Man of La Perouse 1, 11, 179–80

snakebites 10–11, 16, 128–30, 132, 135

trade union affiliation 92, 94

war service 11, 24

wedding 17

zoo employment 22, 24, 26–7, 207, 284

Cann, George (great-grandfather) 2

Cann, George Morris (brother) 57, 117, 119, 171

The Last Snake Man

The Last Snake Man