- Home

- Jimmy Thomson

The Last Snake Man

The Last Snake Man Read online

Snake men: John (left) and his father, George, shelter from the wind and rain while snaking at Dismal Swamp, western Victoria, in 1957. When the weather cleared they bagged 80 snakes.

(Courtesy of Eric Worrell)

Every effort has been made to trace the holders of copyright material. If you have any information concerning copyright material in this book, please contact the publishers at the address below.

First published in 2018

Copyright © John Cann 2018

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publisher. The Australian Copyright Act 1968 (the Act) allows a maximum of one chapter or 10 per cent of this book, whichever is the greater, to be photocopied by any educational institution for its educational purposes provided that the educational institution (or body that administers it) has given a remuneration notice to the Copyright Agency (Australia) under the Act.

Allen & Unwin

83 Alexander Street

Crows Nest NSW 2065

Australia

Phone: (61 2) 8425 0100

Email: [email protected]

Web: www.allenandunwin.com

Cataloguing-in-Publication details are available from the National Library of Australia

www.trove.nla.gov.au

ISBN 978 1 76063 051 5

eISBN 978 1 76063 532 9

Index by Puddingburn

Set by Bookhouse, Sydney

Cover design: Blue Cork

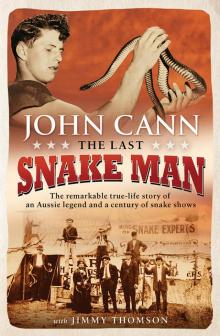

Front cover photographs: John as a teenager (top) and a rural snake show

To my great-great-grandkids,

the ones I’ll miss out on,

so you’ll know where you’re from

CONTENTS

Preface

1 The Snake Man of La Perouse

2 Cleopatra, Queen of the Snakes

3 War baby

4 Underwater football

5 Born to run

6 The Games

7 Race relations

8 Roughing it

9 ‘This one’s dead…’

10 Work

11 Snaking

12 Snakebites

13 ‘He got me!’

14 Showtime

15 Turtles

16 Collecting in Irian Barat

17 A cruel end

18 Back to work

19 Turtle wars

20 My brother George

21 My family

22 Martin Lauer

23 Reptiles and reprobates

24 No fortune, no fame

25 Survivor

Picture section

Appendix Australia’s great snakeys

Appendix John’s turtles

Acknowledgements

Index

George Cann

PREFACE

To the big crowd gathered at the La Perouse loop to watch the snake show in April 2010, it might have seemed like any other Sunday. But whether they knew it or not, they were all about to witness a little bit of history.

This would be the last snake show at the La Pa Loop presented by a member of the Cann clan, the last in an almost unbroken run of nearly 100 years. In that time, nothing short of wars and epidemics, poverty and the Great Depression had kept the La Perouse snake pit closed. To all intents and purposes, through all those years, if there was crowd, there would be a snake man (or woman) with the surname Cann ready to put on a show.

Because that day I may have been the last Cann to perform at the La Perouse snake pit, but I certainly wasn’t the first. My father, George, already an accomplished snake man in his early teens, started the family tradition when he came back from World War I. My mother, Essie—once billed as Cleopatra, Queen of the Snakes—kept it going, albeit reluctantly, when he was on the road doing country shows. My brother George and I then took over after Pop passed away.

And while back in the day there might have been more vaudeville and less natural history in the snake shows, their format rarely changed. We’d bring out the lizards, water dragons and goannas for the kids to see and stroke, and some lucky member of the audience would soon find a python draped around his or her neck. Then we’d get to the serious stuff: the venomous snakes that could kill you with a bite—fatal consequences that had been proved in the past on that very spot.

Yet while the snake show might have remained pretty much a constant down at La Perouse, times did change. I’ve collected written reports—going back to the nineteenth century—of the early days of snake handling in Australia.

Some snake handlers think they’re too smart for snakes—they’re the ones who usually find out the hard way that if a snake wants you, he’ll get you. In the old days, the snakeys, as they were known, would take a bite from a venomous snake to ‘prove’ how effective their antidote potions were. Sometimes the snakes had been milked and defanged (although that was no guarantee of safety), sometimes the snakeys had built up a level of resistance by taking many small bites. Maybe, just maybe, some of the antidotes actually had some effect—but probably not. The term ‘snake-oil salesman’ surely has its roots in these travelling showmen with their dubious wares.

I have video footage of the last public show I did at the Loop. I’d taken down my liveliest tiger snake, one that I would only show now and then because he scared me. He was too good for me, and I knew he’d get me one of these days…if I gave him the chance.

‘I’ll tell you what this tiger snake’s going to do,’ I told the crowd of family, friends, casual onlookers and visiting dignitaries. ‘He’ll wriggle, like this, he’ll come halfway up, and then he’ll bite me on the wrist if he can.’

And that’s exactly what happened. I gripped him by the tail and lifted him. He wriggled, he came up, and he went straight for my wrist with his mouth open, but I rolled him over, and he was back in his bag before he knew it. His intent could not have been clearer. I wouldn’t give him another go.

From the first red-bellied black snake I caught as a kid (earning a clip round the ear from Mum) to that show in 2010, snakes had been a huge part of my life—but they weren’t my whole life. Along the way I also competed at the Olympics and played for New South Wales in the same team as some deadset legends of rugby league. I’ve spent six months collecting animals in the jungles of New Guinea and become a recognised authority on Australian reptiles—and especially turtles. I’ve been a champion boxer, a published author and even appeared in a film with Raquel Welch (well, my chest did at least).

If all that sounds so improbable for the one man that you think I’m spinning you a yarn, then read on and judge for yourself. I hope you enjoy this trip through a rich and varied life. Maybe once you start to read, it’ll be you who says ‘he got me!’

CHAPTER 1

THE SNAKE MAN OF LA PEROUSE

Some people call me the snake man of La Perouse but that’s not quite right. That title belongs to my father, George Cann. Pop entertained and informed generations of visitors to the La Pa Loop, as it was known locally, and he combined the skills of a born showman with the expertise of a scientist. No one knew snakes better than my dad.

Pop was born in 1897, and his family goes back to the old country via New Zealand. There’s a hint of scandal along the way too. His paternal grandmother, Ellen Newman, and her brother Daniel came out from Kilkenny, Ireland, as assisted migrants in 1861. Ellen married James Duruz, from Switzerland, a year later and they had eight children, the last of whom was also James, born in 1876.

Ellen’s son James and my grandmother—confusingly also named Ellen (Cann)—were hooked up in what was more or less a marriage of con

venience in 1897, just a couple of days before my father, Pop, was born on 16 April. Apparently they wed for no better reason than so the kid wouldn’t be illegitimate. There was still quite a stigma attached to illegitimacy in those days. Queen Victoria was still on the throne, so ‘Victorian values’ were as strong as they’d ever be. Soon after, James went his own way and Ellen Cann kept her family name and passed it on to her son, my father, George. Ellen ended up going to New Zealand, where her other family was (and many still are), and Pop was reared by his maternal grandfather, George Cann. Pop saw his real father when he was about twelve years old. He was walking with his uncle Frank, who was about ten years older than him, and a man rode past on a horse.

‘George, you see that man on that horse?’ Frank said. ‘Well, that’s your father.’ It’s the only time Pop ever saw him.

They lived on the corner of Bailey (now Salisbury) and Church streets in Camperdown, where they moved when Pop was about ten years old. He and my mother never used to talk about their pasts, but I reckon it was from Frank that Pop first got interested in showing snakes. I found a newspaper cutting the other day, going back to 1908, about a strike by tram conductors. (Trams figure a lot in my early life—and we were at the end of the track in La Perouse for many years—so it’s maybe appropriate that the trams should provide a clue to our origins as snake handlers.)

It seems the Tram Department had got wind that some of their conductors were on the fiddle, so they’d put plain-clothes special constables on the trams to try to catch them. One conductor had been caught passing tickets that weren’t paid for and he was sacked. The union got involved and demanded he be reinstated and that the use of undercover inspectors stop. Eventually all the tram drivers and conductors went on strike—abandoning trams in the middle of the main streets—and there were fights and mini-riots as the Tram Department employed retired tram drivers to get the wheels rolling again.

Inevitably that led to punch-ups, and that’s where we get our first clue. One newspaper report refers to the arrest of ‘Frank Cann, showman’ for riotous behaviour after a fracas near the junction of Oxford and Liverpool streets. Showman? I’d heard that Frank had an interest in snakes, but this was the first reference I’d seen to him working on the shows. The strike itself—which many were worried would lead to a general strike—fizzled out after a week. The strike leaders and union organisers were sacked, as were all the workers in the power plants who’d joined them. Those were very different times.

So Frank got Pop interested in snakes, it’s safe to assume. But going back to the year Pop was born, something happened out at La Perouse that would change his life and set us, his family, on a track that leads all the way to this book. Round about Christmas 1897, Professor Fox, one of the most famous snakeys of them all, started doing his show at La Perouse. Even back then, La Pa was a bit of a holiday spot for workers from the city looking for somewhere to kick back and have a swim.

It was an area of authentic bush, separated from the spread of houses in the city but accessible to large numbers of Sydney folk, especially after the tramlines were extended there and steam trams started operating. Even now it’s a twenty-minute drive from the city centre, so in the days of the horse and buggy it would have taken the townsfolk a good hour or two to get there. La Perouse was also one of the last areas of Sydney where there was little or no white community. It was an Aboriginal area with its own reserve, and the Aboriginal Protection Board blocked any attempts to build a hotel or pub there.

On Sundays, travelling showmen—some of them little more than buskers—would set up their shows within the Loop around the end of the peninsula. The Loop was the end of the line, literally, for the trams, and it allowed them to turn around and head back to the city. It was as beautiful then as it is today. You have the heads opening out to the ocean, with Congwong Beach on one side and Frenchmans Beach on the other, and the bridge out to Bare Island once home to the big guns that were going to protect Sydney from invaders.

There are a lot more houses around today than there were back then, not to mention the airport to the west and, until 2014, the Kurnell oil refinery now Caltex storage—across the water to the south—but there’s still a strip of bush that runs along the eastern side of Anzac Parade that would have stretched all the way down to the ocean cliffs before the NSW Golf Club built its course there in the 1920s. The Cable Station, which now houses the Laperouse Museum, was where the telegraph cable linking Australia and New Zealand first came ashore and where telegraphers were trained in the late 1800s.

The Macquarie Watchtower is still there, but the fence of our old snake pit is all that remains of the once popular funfair. You can still imagine the Loop coming to life at the weekend when the show people moved in, though. Like many a tram terminus around Sydney, it became a magnet for daytrippers desperate to get out of the city and, of course, those who were happy to provide them with entertainment and refreshment.

They had trick shooters, jugglers and traditional sideshows like puppets and minigolf. Kids would dive from the wharf into the water to catch pennies thrown by visitors before they hit the sand. A couple of likely looking Aboriginal boys would be paid to box each other for the crowd’s entertainment. There were stalls selling Aboriginal art. And there were snake men.

As I detailed in my book Snakes Alive, there’s a long and honourable tradition of snakeys in Australia, ranging from those with a naturalist’s knowledge of reptiles to some who were, literally, snake-oil salesmen putting on a show just so they could sell their highly dubious potions. The first of them as I said earlier, was ‘Professor’ Fred Fox who, initially in a roped-off area, then later in a tent, would show his snakes and sell his ‘miracle’ snakebite ointment. When Fox died in India from a snakebite—a story I’ll come back to later—other snakeys carried on the show on the spot where he used to pitch his tent.

Now, Pop was a real runabout as a kid, much to the distress of his grandparents, and by the time he reached the age of ten he’d roam the city alone, often ending up out at La Pa. The tramlines were extended to La Perouse in 1902, so he’d find his way out there, probably jumping on and off the running boards to get a free ride. It was while he was snooping around the bush looking for snakes that he met up with Snakey George. Yes, I know, another George; it’s like they had a shortage of names back then. Anyway, the boy and the 50-year-old man struck up a friendship that caused even more trouble for Pop back home.

Snakey George was, to all intents and purposes, a hermit and looked the part, with his straggly beard and shabby clothes. He lived in a shack—little more than a humpy, really, with a tarpaulin roof weighted down with huge rocks—in thick bush at the northern end of the beach at Little Bay, near the La Perouse peninsula. George came to look forward to visits from Pop, who often stayed on weekends while they wandered the bush collecting snakes and reptiles to sell to snake showmen, museums and other educational institutions.

Snakey George would track them through the bush or find them resting, especially under sheets of tin or corrugated iron, some of which he had left around for that very purpose. As a youngster, Pop became fascinated with the capture and handling of these often deadly creatures and teamed up with Snakey George whenever he could get out there.

When Pop was twelve he caught a large red-bellied black snake in the lagoon that still exists at the northern end of what is now Pioneers Park, near St Spyridon High School. You still get red-bellied black snakes there; I know because every summer I get one or two calls to come and remove them. Anyway, when Pop took his snake home, his grandfather gave him a hard time, so Pop gathered together his belongings, including his reptiles, and ran away. With the little money he’d saved from selling snakes—Snakey George always split the proceeds from selling the specimens they caught together—Pop had enough money to buy a square canvas snake pit and start showing snakes himself at Hatte’s Arcade in Newtown.

Back then, Newtown was the main shopping centre outside the city itself, and people travel

led for miles to shop there, mainly because it had everything you could want within a relatively small area. Hatte’s Arcade was a local landmark, and as well as clothes shops, it housed the offices of a local newspaper, a watchmaker and a billiard room.

Significantly, it also had a small picture house (film theatre) and a penny arcade, with amusements costing only one coin. It was the perfect place for a young showman to first ply his trade. It soon proved, however, a bit too close to Pop’s grandparents, who lived just a few streets away, so he struck out for Melbourne, then the ‘snake capital’ of Australia.

Not surprisingly, young Pop was bailed up by the coppers while doing his show in Bourke Street. The newspapers were full of stories of snakeys who hadn’t survived bites, and the police didn’t fancy being held responsible for the death of a kid, so Pop was sent back to Sydney. He was still only twelve.

As he was clearly beyond the control of his grandfather, Pop spent a spell at Mittagong Farm Home for Boys, where lads convicted in the Children’s Court were often sent. I have no idea what he was convicted of, but somebody probably decided he needed to be brought under control for his own safety. When Pop came back to Sydney, he returned to Newtown but still spent most of his weekends in the La Perouse–Botany districts. He even sold snakes on the sly to Professor Fox.

Just before the Great War, Professor Fox set off for India via what is now Jakarta, to demonstrate the effectiveness of his snakebite antidote to doctors and scientists. He left the La Pa snake pit in the care of his good friend Garnett See. Maintaining an active presence in the snake pit was the only way of holding it for future use. There were plenty of other snakeys who’d happily take over a valuable patch like that one, so it was better for him to have a friend there than to leave it to whoever might claim squatting rights.

It was an ill-fated bequest on all fronts. Garnett See came from a well-to-do family and his late uncle John had been premier of New South Wales in the early part of the century. Pop, who was only sixteen, witnessed See’s one and only show at the La Pa snake pit. The first day, a brown snake got him and killed him. I found his grave three or four years ago and it’s unmarked, so I suppose he must have been the black sheep of his family. The grave is about to be re-used, if it hasn’t been already. There’s nothing there, and it’s not maintained.

The Last Snake Man

The Last Snake Man