- Home

- Jimmy Thomson

The Last Snake Man Page 19

The Last Snake Man Read online

Page 19

Gary had been a record-breaking distance swimmer as a kid but had dropped down to the sprints because Murray Rose was on the rise and Gary wanted to increase his chances of a medal. In fact, Gary got bronze when Australia completed a clean sweep in the 100-metres freestyle.

And that’s what puzzled me. He was a champion swimmer and an experienced fisherman with a good boat, and he had a mate with him, but they were both gone. The boat drifted in but they never found the bodies.

Yes, I know there are freak waves and if one bloke gets into trouble he can take the bloke that’s rescuing him down with him. But I can’t help wondering if they were in the wrong place at the wrong time. And I often wonder what the blokes in the powerboat would have done if they’d spotted Trevor and me or we’d gone into their cove. They would surely have heard our motor and if it had been a drug drop, who knows what they’d have done?

It’s all ifs and buts, but I’m putting that down as a bullet dodged, for us if not for Gary and his mate.

CHAPTER 24

NO FORTUNE, NO FAME

Although we kept the snake show going for four decades after Pop passed away, George and I never made that much money from it. On a really good day, we could get $200 when we passed the hat around at the end of the show, but that was the exception rather than the rule, and it barely covered our expenses for catching and keeping the snakes. There was an interesting and fairly lucrative sideline, however, that led to us both ending up in Hollywood movies.

I can’t remember exactly how it started, but there were a lot of kids’ TV shows with nature segments in them—and youngsters are fascinated by snakes and lizards. Naturally enough, when they were looking for someone to demonstrate snakes, they came to us, just as they used to call Pop for that sort of thing. After a while it made sense for us to put a listing in The Production Book, a trade directory for anything and everything to do with TV and film production. You want a lighting technician or a set designer or a make-up person—or a snake wrangler—you go to The Production Book.

We provided snakes for lots of TV dramas; snakes have been part of Australian storytelling as far back as Henry Lawson and Banjo Paterson, and they make for scary TV. So they’d call me or George up and ask if we could supply snakes and, of course, look after them on set. I used to supply brown snakes and tiger snakes for a lot of the different TV shows, and commercials as well. I had spiders and lizards too, and on any given day I could be driving around with a tiger snake and a couple of turtles in my car.

The movies were the best-paying gigs, though—money is no object for those fellas. One production in Queensland wanted to use a big sea turtle, but the Queensland wildlife people wouldn’t let them because they were a protected species. So they called me and asked for the biggest turtle I had.

They flew me up to Queensland and flew me out to the island, but the weather was too bad for filming. So there I was, stuck in a motel with a bloody huge Mary River turtle. So I put some water in the bath and let the thing swim around in there, but I forgot about the room-service maid, and when she came in to clean the room she got a bit of a shock when she went in the bathroom.

I apologised profusely but she said it was okay and asked me what I fed it. I said bananas, and the next thing, the maids were in the bathroom, feeding bananas to my turtle. The weather got no better so they flew me back to Sydney, but before I could get back, an environmentalist group complained about me flying a turtle up to Queensland. Then the Queensland government got involved and they refused to give the movie producers permission to bring a turtle into the state. My turtle and I got a good trip up there the first time, anyway. And I was well paid and the turtle was well fed.

My biggest brush with fame came in 1988–89 when they were filming a telemovie called Trouble in Paradise, starring Raquel Welch and Jack Thompson. Raquel shot to fame in 1966 as the star of 1 Million Years B.C., and she was still in pretty good shape at close to 50 years old. The movie was about a posh American woman who is shipwrecked on a desert island with an uncouth Aussie yobbo, played by Jack Thompson.

At one point, Jack’s character is supposed to have this big, hairy spider crawling all over him, so they paid me to get a big bird-eating spider. I got one from my mate Peter in Queensland. The bird-eating spider rarely eats birds, but it’s big enough to, and its fangs are huge and, although its venom isn’t the deadliest, it can give you a nasty bite.

‘Are they cranky?’ I asked Pete.

‘Oh, they can be,’ he said. ‘If you want to handle them you’ve got to use a big wooden spoon and pick them up that way.’

So I put the spider down on my back lawn and tapped him with the big wooden spoon. Was he cranky? He reared up like a funnel web, waving his front legs and showing his fangs and I thought, ‘Jeez, this is going to be interesting.’ When I picked him up on the stick, though, he was all right. Down we went to Darling Harbour, where they were shooting the dockside scenes, and the stuntman who was going to be Jack’s stand-in, came up and said, ‘Give us a look at this spider, John.’

I tipped the spider out and the stuntman was clearly taken aback at the size of it.

‘Does he bite?’ he says.

‘Oh, I don’t think so,’ I replied. ‘Just handle him gently and you’ll be fine.’

I gave the spider a gentle tap and he reared up again, like before, all fangs and furry legs.

‘No f…n’ way!’ said the stuntman. ‘No way am I going anywhere near that!’

He walked over and told the assistant director he wasn’t touching the spider. End of story. Then the AD came over to me and asked what we could do. I shrugged—I’d done my bit. I wasn’t there to wrangle the stuntman.

‘Would you do it?’ he asked.

‘Yeah,’ I said. ‘If you pay me enough.’

And so I was paid both for providing the spider and for standing in for the suddenly spider-wary stuntman. Best of all, it was Saturday and I was supposed to be working at ICI on double time but my mates covered for me, so I got double time for my day job and double time for the spider.

All I had to do was lie face-up with my shirt off. They darkened me up a little bit with make-up. Even though I was pretty brown, I wasn’t as dark as Jack because he was supposed to be in the sun all day. Then they put his medallion chain on me and that’s what you see in the movie as the spider crawls around and up my neck and around my ears.

If you’ve ever been on a TV or movie set, you’ll know that they keep doing the scenes over and over again, and there must have been about ten takes of this spider crawling all over me. I’d had enough already when the spider decided to wander off.

‘No, bring him back again, John,’ one of the crew says.

‘You friggin bring him back,’ I said. As if I was going to go and pick him up and put him on my neck. But it was all right and I got good money and it went over pretty well.

As for meeting Raquel, I remember they had a bar room set with fake cigarette smoke pumped into it and lots of Chinese actors and extras to make it look like it was in Hong Kong. I was sitting out on the verandah with a couple of the Asian extras who’d come out for a breath of fresh air, and the next thing out came this gorgeous woman. She stretches out her arms and breathes in deeply, showing off her assets.

‘Oh, I detest that smoke,’ she says to me. ‘It’s killing me.’

So here’s my chance to say something clever and witty, maybe even a bit flirtatious, to one of the most beautiful women in the world.

‘Yeah,’ I say, ‘it’s not real pleasant, is it?’

Not real pleasant?! Chance of a lifetime and I was tongue-tied.

George went one better than me the following year, not in talking to a Hollywood heartthrob but in appearing in a proper made-for-cinema movie. The film was Quigley Down Under, with Tom Selleck (then famous as Magnum PI) in the title role and the late Alan Rickman as the baddie. I don’t know exactly what George’s role was, but I doubt he was as easily flummoxed by the stars as I was by the lovely Ms We

lch.

CHAPTER 25

SURVIVOR

By the time you read this book, I will have celebrated my 80th birthday (I hope) surrounded by my family, camped on the upper reaches of the Macleay River. If writing this book has taught me anything, it’s that I’ve had a pretty eventful life. I’ve competed in one Olympic games, where I made lifelong friends, and was part of the torch relay for the Sydney Games in 2000. I’ve acquired a shoebox full of athletics medals, played rugby league for New South Wales with some legends of the game, and fought deadset champions in the boxing ring.

I’ve survived rickets, snakebites, a broken neck, a stroke, cancer and being shot at by Indonesian soldiers in New Guinea. I’ve been ripped off by kids who went on to be killers, cheated by bungling bureaucrats and robbed by corrupt officials…and a charming young woman on a German train.

I’ve written nine books and a stack of scientific papers, and identified many new species of Australian turtle, occasionally making waves. I’ve been invited to give the keynote speech at conferences in the United States, where hundreds of my peers turned up to hear me, and I’ve given a talk to an empty room in New Zealand.

Somewhere along the way, I acquired a brilliant family: my loving wife Helen, three great kids and eight grandkids (not one of whom has the slightest interest in snakes!).

In 1992, I was awarded the Order of Australia for ‘service to conservation and the environment, particularly through natural history, and to the community’. It was Keith Smith, who compiled the two volumes of Johnny Cann: Nature Boy, who got the ball rolling. The first I heard of it was when I got a letter asking me if I’d accept the honour if it was offered to me (they don’t want to offer it to someone who might throw it back at them).

So on a beautiful autumn day on 1 May 1992, Helen, Paul and I went to Government House in Sydney, where I was invested in the Order of Australia by the New South Wales Governor, Rear Admiral Peter Sinclair. It was a proud moment that many would take as the culmination of their career—but I still had a few years left in me.

I carried on doing the snake shows, alternating with George until he became too ill to continue and then passed away. My last public show at the Loop was in April 2010. The federal MP Peter Garrett and state MP Michael Daley were both there and presented me with a plaque and certificates. There was a big mob there that day, with TV cameras (one of my friends from down south who was too sick to attend paid for a professional film crew to record the event for him), the lot, and I only did three shows. I was pretty slow but it was quite good.

We had a big party after. It wasn’t organised but it just spontaneously occurred in my backyard where there wasn’t even standing room. A lot of my mates came from interstate for the last show, including one who came down from Darwin. We had a pretty good night.

I think I might have got out of the snake game just in time. Two years later I suffered a pretty serious stroke, and when the doctors did a scan to see what damage had been done, they reckoned they’d found cancer in my kidney and my brain. I don’t remember much about that conversation—I wasn’t thinking too clearly—but all my family was standing around nice and quiet, and whispering to each other and to the doctors, as well as to me.

Eventually, Paul, my elder son said, ‘Well what’s the bottom line, Doc? Give us the results.’

‘With the cancer in his brain and his kidneys, I consider that your father has got about two and a half weeks to live,’ he said.

My youngest bloke Jace is a really quiet kid, but Paul and Helen had to grab him and pull him away because he was about to have a pop at the doctor for being so blunt in front of his mum. Later on I discovered that Paul had asked the doctor if the two scans showing the cancer were the same colour. The doctor looked surprised and said, ‘No, no they’re not.’

‘Well that doesn’t mean they’re both cancer, does it?’ Paul said.

‘You could be right, Paul,’ the doctor said.

Afterwards they decided it wasn’t cancer in my brain after all, and after six months of investigation the surgeon decided it was actually the bleed that had caused the stroke. That said, the Prince of Wales Hospital staff, the specialists and the doctors were pretty good. I was in hospital for a few weeks and then when I was strong enough they removed the diseased kidney, and then everything sort of came good.

I still wonder whether it was a cancer or a dead kidney, to tell the truth, because tiger snake venom can kill kidneys—the Commonwealth Serum Laboratories have done papers on it. I did mention that to the doctors. A very good snakey mate of mine called Vic Hayden had a stroke, same as me, and we were on the same tablets, but five months later Vic was stone dead with complete kidney failure. It was the tiger snake that killed Vic.

A couple of days after I had the stroke I was supposed to be going to the Galápagos Islands. A mate of mine is a professor at Chapman University, in the city of Orange, California, and they had raised funds so that a number of us could fly out and go on a big cruise boat with a group of students. Helen didn’t want to go so Jace was coming with me. That was naturally called off when I had the stroke, but twelve months later they said, ‘Well, you can come this year.’

So in January 2013, Jace and I went there and I celebrated my 75th birthday aboard the cruise boat, the Tip Top II. We were out diving nearly every day on that trip. At one point I went down 5 metres and Jace took a picture of me with his underwater camera. I just put my thumb up in the air and rolled over on the coral. I got a mate to email the picture to the doctor who’d said I had two weeks to live. I didn’t put my name on it—just my patient number at the hospital, which I know off by heart, I’ve been there that many times. I know he received it and that if he was curious, he would have looked it up, but he never replied.

So, as I approach my 80th birthday, I’m doing all right for an old bloke. My new book on turtles came out last year and I’ve been having operations on my eyes, which have delayed another trip to America, but that will be back on soon.

The venomous snakes have gone from my pits. You have to be on your toes and have your wits about you, especially when your next snakebite could be your last. But my old mate the water dragon is still out the back, nodding his head as he soaks up the sun.

A couple of people from the herpetological society have taken over the snake shows at the Loop, but for the first time in 100 years, there’s no one there with the name of Cann tempting fate and wondering if the next tiger or brown will be the one that gets him.

So you can still catch a snake show on a Sunday in the pit at La Pa. But I am the last of the snake-handling Canns, happy to make way for the next generation of snakeys to inspire and amaze the kids who will continue this great tradition.

PICTURE SECTION

George Cann, my pop, aged sixteen, already a fully fledged snakey.

My mum, Essie Bradley, also sixteen, as Cleopatra, Queen of the Snakes.

The La Perouse Loop in 1910. It was the roundhouse shop owner George Rodgers senior who persuaded Professor Fred Fox to set up the first snake show at La Pa at Christmas in 1897 to attract customers.

Snake bite antidotes were the stock in trade of the snakeys, but Professor Fox’s couldn’t save him from the deadly krait.

Snake handlers were enormously popular at travelling shows—this group had come all the way from America.

Essie and George at La Perouse—Mum was never all that keen on snakes, not that you could tell.

Macquarie Watchtower and Customs House at La Perouse, where I was born in 1938, photographed in the same year.

Me at two years old, with my pet python ‘Fang’.

With my sister Noreen and our pet wallaby.

Our first house at Yarra Road, with Hill 60 and the power station in the background, in 1946.

Pop in 1934 in the backyard snake pit at Yarra Road.

My brother George holds me up, trapeze-style, in front of the snake pits.

Pop Cann at the La Pa snake pit, in the 1930s. Note the ‘safety’

fence and the ‘Sunday best’.

Back from a trip to Lake Cowal, Pop adds some tiger snakes and a few browns to the snake pit. (Pic: Eric Worrell)

As a teenager, chasing a goanna on the dunes at the back of Congwong Beach near Botany Bay. (Pic: Eric Worrell)

Keeping a watchful eye as I handle a red-bellied black snake. (Pic: Eric Worrell)

Pop Cann, with a New Guinea python, as Curator of Reptiles at Taronga Park Zoo. (Pic: Eric Worrell)

The NSW team (including Betty Cuthbert and a thirteen-year-old me) arrive in Hobart for the 1951 National Schools Athletic Championship.

In 1954, aged sixteen, winning the Australian junior 220 yards championship, in South Australia. My time qualified me for the men’s heats and final. (Pic: Keith Short Collection)

Winning a 220-yard club race in Sydney just prior to the 1956 Olympics, beating two sprinters who were selected to compete in the games as well as the state champion. (Pic: Keith Short Collection)

Qualifying for the Olympic decathlon, I attempted the high hurdles and won. My friend, state champion Keith Short, was beaten for the first time in a year. (Pic: Keith Short Collection)

‘Gangway the Cann Way’: a keen cartoonist, Keith Short poked fun at my technique…or lack of one.

This long jump of 7.44 metres was the best recorded for eight years. It convinced me to try to qualify for the Olympics in the individual event but I was injured in my first attempt.

A ticket to the Melbourne Olympics, which would cost $33 in today’s money—a bargain!

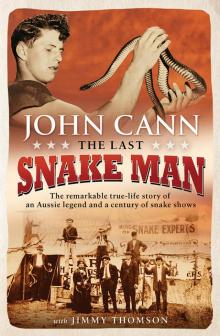

The Last Snake Man

The Last Snake Man