- Home

- Jimmy Thomson

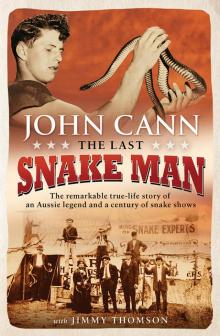

The Last Snake Man Page 16

The Last Snake Man Read online

Page 16

The crowds in America are usually pretty big because the reptile societies have large memberships. I’ve been both an ‘also-ran’ and top of the bill as a keynote speaker. There as here, there’s a little bit of a division between the pros and the amateurs, although in one society there the pros and amateurs joined forces.

At one of the meetings in Orlando, Florida, there had been a hurricane a few days before and one of the top amateur turtle breeders in the world, a real conservationist, had suffered a lot of damage with all his pens and walls blown down. Luckily his house was missed, but there were trees across his roadway and a lot of damage to his turtle areas.

One of the boys suggested we go and give him a hand. I think nineteen of us were amateurs, and every one of us went down to his house to help him clear up and get everything back together. As far as I know none of the professionals went. No doubt people did have flights booked to go out straight after the conference, but it upset a lot of the amateurs. Ironically, this conference was partly intended to fix up all the differences between the amateurs and pros. These days it’s all a bit more free and easy—amateurs are welcome at the professionals’ meetings and vice versa.

After I’d been in Orlando, I got an invitation to dive and give a talk at the Nuclear Research Station on the Savannah River in South Carolina. It was an honour to be invited by Dr Witt-Gibbens, undoubtedly one of the top guys in his field. However, even with permits I had trouble getting through the gates—this was one of the highest security areas in the States. The meeting and the diving in the Savannah River went for a couple of days, but they took me off site to sleep in a motel and that was fair enough. The top brass knew I was no risk—when I took my golden handshake from ICI back in 1987, one of the managers told me I’d been checked out by the FBI. Just as well they never knew I once lived next door to a communist!

I have to say that over the years I have stirred up my fair share of controversy and there are a few people—both scientists and hobbyists—who disagree with me. All I can do is quote a mate of mine, Professor Gunther Thieschinger, who says: ‘How can you conserve an environment when you don’t know what is in it? Without identification and description you have a language without words.’

One of the problems is that, although some scientists make their living working on turtles, as far as I’m concerned they don’t fully understand them. Some seem to wait for DNA results and then do the writing or descriptions.

So what is a species or subspecies? Who decides such things and when? Many scientists don’t believe in classifying subspecies, but if populations are geographically isolated and distinctly different, both morphologically and biologically, but when brought together could still produce fertile offspring, then I believe they warrant their own status as subspecies, chiefly for conservation purposes.

There’s danger inherent in accepting isolated facts without examining the wider context. Take the eastern snake-neck turtle (Chelodina longicollis), for example. A scientist found 300 specimens in the field and stated they were safe, but given that John Goode, Dr Col Limpus, Charles Tanner and I had previously found thousands of them, this 300 figure actually represented a dramatic decline in the population. Col Limpus says the species is virtually extinct in the Brisbane metropolitan area.

The evolutionary ‘trees’ for turtles constructed using DNA evidence have seen numerous changes over the last fifteen years and there are likely to be more in the coming years. Why? Because some scientists are relying almost solely on the genetic results to determine species divisions and relationships with very little reliance on other knowledge.

Using five different genes, one of the world’s top DNA experts has stated that Chelodina canni and C. rankini are 2 per cent different, yet other scientists still maintain that they’re the same species. Morphological differences within the saw-shell turtle (Wollumbinia latisternum) complex are tremendous, yet scientists relying on genetics alone continue to regard them as a single species.

There will be accepted changes in the future. The original species concept still used by some scientists says that the different turtles will not interbreed, but of course, they do. The northern long-neck turtle (now m. Chelodina (macrochelodina) oblonga regosa) and C. canni will naturally hybridise where they overlap, as will Georges’ turtle (Wollumbinia georgesi) and a locally occurring or introduced species of Emydura in the Bellinger River, but they’re still regarded as distinct species. While the information provided by DNA analysis is an advantage in many ways, it should be used in combination with morphological and biological characteristics.

Morphological and biological differences such as size, babies, number of eggs and eye colour are all important, and some morphological differences become more distinct in aged specimens or are best seen in hatchlings. Some scientists claim that most of the populations of Emydura macquarii in different river systems on the east coast are all the same, but in my view they’re not. Based on the features of their morphology and biology, these warrant being treated as separate subspecies.

From a conservation point of view this is important, as some of these populations may be at risk and this is ignored while they’re all viewed as identical. Four of the subspecies of E. macquarii have been rejected by some—but these beautiful turtles need acceptance and protection.

The criticism from institution-based turtle researchers regarding the legitimacy of the species of turtles I have described has, in my opinion, not been justified. In describing new species or subspecies I have taken into consideration a range of characteristics that includes their morphology, biology and the extent to which they are isolated from other species—not just their genetic similarities or differences. The description of these new species is important for their conservation and, with the threats they face these days, far more than just an academic exercise. I think attitudes will change with the publication of my 2017 book (with Ross Sadlier), Freshwater Turtles of Australia.

I have mates for whom conservation and photography, rather than collecting, are the main focus these days and I’ve been up north with them four or five times. I fly to Cairns and then we take four-wheel drives up to the Gulf Country or the Cape.

For collecting, I’ve made a couple of major trips up in the last few years to Cape York with Origin Energy and my mate Alastair Freeman of Aquatic Threatened Species in the Queensland Department of Environment Protection and Heritage. He was interested in the endangered species and we were working on the flatback turtles with the local Aboriginals.

The biggest problem up there are the thousands and thousands of wild pigs digging up turtle nests and devastating the turtle population. One pig there kept digging eggs up and they could never catch him—he was too smart for them. When they finally shot him and opened him up, they found 30 or 40 dead baby flatback turtles in his belly.

Origin Energy are a bit on the nose with a lot of people in the conservation world, but I have to give it to them: they hired a helicopter and snipers and they shot hundreds of wild pigs over a couple of seasons.

Freshwater Turtles of Australia is the culmination of decades of interest in and study of turtles. I have thousands of turtle photographs to sort out, and many of them have never been mounted or even looked at, so I’ve handed them all on to Ross Sadlier. He has 2500 of my turtle photos on his computer already.

So, yes, maybe my family are right and my hobby did become an obsession.

CHAPTER 20

MY BROTHER GEORGE

My brother George Morris Cann was born in July 1927 at Hill 60, Yarra Bay. Soon after, our parents needed somewhere more substantial to live so they built a place on the hill. The only photograph I ever saw of the house was the large deep sand pit that had been built for snakes, with the house in the background. The houses and shacks are long gone from the hill. It was around 1936, after Noreen was born, that the family moved to better accommodation in the Customs Building at La Pa closer to the display pit for the snake show.

By the time I came along in 1

938, George was eleven years old and was already travelling with Pop, whether it was for catching snakes or to help with shows. But the following year travelling to shows came to an end, when Pop accepted the position of curator of reptiles at Taronga Park Zoo. Opportunities expanded in another direction, however, when Pop persuaded the police to lift a ban on showing venomous reptiles, and showmen could ply their trade at the Sydney Royal Easter Show for the first time in many years.

Things were on the up for the Canns. In 1940 we moved to our current home in Yarra Bay and Pop built massive above-ground snake pits that could hold the 200 tiger snakes that Eric Worrell and Ken Slater collected to be milked for venom for the Commonwealth Serum Laboratories.

Because of the age difference, George and I never hunted snakes together when I was young, and I don’t recall him hunting too much with Pop until he got older. I recall one time when George and I went to the Chinese Gardens at Botany, a few kilometres from where we lived, to catch golden bell frogs. They’re now classified as an endangered species but at the time they were common. They were in water wells made from railway sleepers and there were dozens of them. One time George collected 100 and I caught about 60—these were Pop’s food for the snakes in the pits.

After Pop bought his Ford ute, the three of us travelled to various places, such as Lake George, together. We always caught a few snakes on our one- or two-day trips, but we never ever took any home. It was just a good day’s outing.

Sometimes we went together to the Barmah Swamps on the New South Wales banks of the Murray River. Once we were there the day before the duck season opened, and there was an occasional car passing on the bush tracks, obviously looking for a good shooting location. We were there sitting on a log having coffee, waiting for a bit of heat to bring out the tiger snakes, when a car with a few people in it went past us and stopped a bit further along around a corner. A few moments later, we heard an ear-splitting scream and I said, ‘Come on, George. The snakes are out.’ We went around the short bend and there was a lady climbing over the log and pulling up her dacks. I jumped over the log and sure enough grabbed the big nice-banded tiger. One of the crowd of people in the car said, ‘How come you knew there was a snake there?’

George and I looked at each other. ‘Why else would she be screaming?’ I said.

In his younger days, George was extremely fit. We regularly had footraces around the blocks. Skipping was all the go in those days and I never did any, but George and his mates did and all they were pretty good, like the top boxers. In fact, a mob of them, George and his army mates, used to box at Woolloomooloo Police Boys’ Club. George was a good boxer—a welterweight, I think—and whenever he went there he used to spar with Jimmy Carruthers, who would later be a bantamweight world champion. Les Dorry was the trainer and he also trained me, Les Davidson and Willo Longbottom, when we went there instead of our usual Kensington or Kingsford Police Boys’ Clubs.

George had never had any intention of being either an amateur or professional fighter. He was just keeping fit. Somewhere kicking around I have a cup he was awarded when he won the army championship on HMAS Kanimbla, a cruise ship that had been converted into an armed troopship during World War II. Then he went to Japan and somewhere along the line he won another title, but that was it. He never fought again.

George was called up to the Australian Imperial Forces on 7 August 1945 and began his jungle training at Canungra, Queensland. He was in luck. The Japanese officially surrendered a week later (Germany had already surrendered a few months before). George’s army days had a long way to go, however—he wasn’t discharged until September 1948, and his service was listed as 351 days in Australia and 650 days overseas.

At various times he was stationed at Bougainville or Rabaul Prison hospitals as an orderly. While he was there a high-ranking Japanese officer in George’s section committed suicide using a knife to cut his own throat. The Japanese officer still had his uniform on and George acquired all the ribbons that he’d been wearing. Years later, he showed them to me, with their black bloodstains still clearly visible.

Besides Bougainville and Japan, George was stationed in Germany and England. While in Germany during the occupation, George and a few mates went to visit a tourist town that had survived the Allies’ bombs. The town was Hamelin, best known for the legend of the Pied Piper. The three diggers had a meal at the famous old restaurant pub, called the Rattenfängerhaus. George brought home the menu, which had nine pages of text and pictures relating to its history.

George did his snake displays at schools, shopping centres and showgrounds, as well as TV ads and film work. We collected snakes together all over the place, including on Flinders and Chappell islands in Tasmania, and at Lake George near Canberra. We had a competition every day for the first, the biggest and the most caught, with a prize of a beer for the winner of each category. The first snake caught was important because if the weather was bad and only one snake was caught, that was all three categories won and the loser had to buy the winner three beers.

George was bitten by snakes ten times. Once he was bitten by a brown snake at La Pa and they took him away in an ambulance. Someone came rushing over to my house to tell me and luckily I was home, so I whipped up to the hospital and went straight into the emergency room. I knew where it was—I think I might have been in there once or twice myself. I walked in and George had a pressure bandage on his arm, which was then the new treatment, with a nurse and a sister watching him.

‘How are you?’ I asked.

‘Oh, no trouble at all,’ he said. ‘I don’t even remember passing out.’

‘No antivenom?’ I said.

‘No, not at this stage,’ he said. ‘I don’t think I need it.’

In came the doctor and said to the sister: ‘I think it’s been an hour now. You can take the pressure bandage off.’

‘Hang on, Doc,’ I said. ‘Don’t take that pressure bandage off. You’ve got to have antivenom on standby if they’re going to take the pressure bandage off.’

‘Don’t tell me how to do my job,’ he said.

‘I’m telling you,’ I said. ‘You don’t take it off without having antivenom on hand, just in case.’

‘Get out or I’ll call security,’ he said.

‘Okay,’ I said. ‘But I’ve warned you.’

As I was walking out the door I heard the sister say, ‘Doctor, he knows what he’s talking about. You need the antivenom.’ As I was sitting outside I saw one of the sisters come past with the antivenom out of the fridge, just in case. But they didn’t need it. They kept George there for another couple of hours before I took him home.

George survived the snakebite but he wasn’t immune. He’d have needed to take several small bites regularly over a long period for any resistance to develop. Graeme Gow, our mate from the Top End, was bitten a lot and he reckoned he was immune from snakebite, but when Dr Struan Sutherland checked his blood, he said he had no resistance in his system at all. He survived a lot of bites, but on at least one occasion he was in trouble and needed antivenom.

Before George retired at 65, he worked as a plumber and fitter for Wormald Brothers who were a fire protection firm. One of George’s jobs was to go each fortnight to the James Hardie factory and dust the asbestos off the fire valves and pipes in the ceiling. There’s no doubt that dust led to him contracting mesothelioma.

George died on my birthday, on 15 January 2001. Some people think I’m heartless when I say it was the best birthday present I ever had, but then they probably never had to watch someone they care about dying a slow and horrible death like that, literally fighting for every breath.

Voice of the bush—a tribute to George Cann

by Neville Burns (extract)

Well, I got the news this morning, mate, that you had gone away

The tears were running freely, I’m not afraid to say.

But we were blessed to know you, George, though we are now apart

And the many things that made you s

pecial now live on in our hearts.

The humour, kindness and mateship that you showed to everyone

Were known throughout the country, mate, and now your race is run.

A part of Aussie tradition goes with you, we all know.

The last of the travelling snake men, who lived to do his show.

A man known by sight to thousands who visited ‘The Loop’

On a Sunday afternoon at La Perouse, you’d always find a group

Of people gathered round ‘The Pit’ to watch the snake man with snow-white hair.

Yes, there will be many who’ll miss you, mate, now you can’t be there.

The Cann family tradition that has been around so long

Started by your Dad many years ago, and carried on by you and John,

A tradition you were proud of mate, and so glad to be a part

A symbol of the love for your Dad that you carried in your heart.

I wonder how many people knew, George, that in your pocket at each show

You always tucked a piece of cord, used by your Dad all those years ago

A very moving gesture, of love and deep respect

A bond that sadly in this world so many would neglect.

With a lively sense of humour, strong in the way a man should be,

To many a younger man and inspiration, as you surely were to me.

If a mate was feeling badly, they could count on Georgie Cann

He’d always be the first to lend a helping hand.

And now you’re gone from us but our memories will never cease

We just want to say George, dear old mate, rest in peace.

CHAPTER 21

MY FAMILY

As you know, I first noticed Helen when I was working at the hospital just before the 1956 Olympics and she worked on the big ironing press in the laundry. I noticed a really good-looking sort and in disbelief my boss pointed out that she lived across the road from me.

The Last Snake Man

The Last Snake Man